Dear readers,

My experience of Moscow started to improve in mid-April, and by early May I would admit, with some fastidiousness, that it had even begun to grow pleasant. The sky in Moscow starts to open up in the spring, and its many deciduous trees, which one does not notice during the winter, burst into bloom. Running outdoors becomes more pleasant. Fluff from the blossoming poplars carpets the streets so thickly that it looks like wool. One accepts, in the spring, that Russia is a country in which nothing works and nobody cares. The trams go more or less where they are supposed to. Short-haired Central Asian men in neon orange safety vests sweep dust from the edge of the roads. One takes greater notice of the trams, cleaning men, and soft, orange sunsets, which go for so long that it seems that they could stretch into the following morning.

I had a lot of friends in the dormitory. By the end of the year I was not baking as much as I had been. The halls of the dormitory were now hot and bright, and people came and went more frequently, preparing to go home for the summer or to stick around, the place half-empty and silent. People now stood outside smoking and chatting until all hours of the night. My work was going more or less indifferently. I was mostly looking forward to getting out more over my last few weeks and trying to make summer plans at this point. The whole month of May had a certain laziness to it, a sense of gentle passage into something indeterminate and unimportant, as though it did not matter where the month or I ended up.

One of the fruits of my efforts to get out more as the end of the school year approached was a pair of trips to friends' summer homes. One trip was for a day with an artist friend who had invited her family, other artist friends, and friends of those friends, so that the company was large and, to my way of thinking, somewhat impersonal, which did not really bother me. I tried tea made from a real samovar there, and I sat with my friend's father, mostly silent, as he heated the water for it over an empty fire, stuffing pine cones into a slot where they turned to ash and helped to heat the water evenly, or something like that. We ate and laughed a lot that day, and, with little else, to do, took a short walk. The idea of a visit to one's summer home is to escape the noise and crowds of the city, and this we accomplished, so that I felt as though I had entered a different country.

My second trip to a summer home was, perhaps, even more interesting. I went this time with relatives of a friend, his two female cousins, both roughly my age, and the one's six-year-old daughter. Their summer house was not as developed as the first one that I had visited--it was newer, and, as one of the women with whom I went pointed out, they did not have a man around to help them. The road leading up to it, once we had exited the highway for a paved road and the paved road for a dirt one, was an unmaintained field where part of the grass had been flattened previously by tire treads. The summer house was surrounded by a wooden fence--it was the first thing that they had erected once they had bought the plot, my friends' cousin explained--and it included a toolshed, a little greenhouse, some vegetable plots, and a lot of weeds. The house itself looked like a barn, from a distance, and had a wooden front porch. It had not yet been outfitted with plumbing or electricity, but it had a sort of indoor outhouse that was treated so as not to stink, and it was supplied with water (non-potable unless boiled) from its own well.

This trip was more interesting than the other in part because there were only only three other people to interact with, one of whom did not really count, as she was a child, and because nothing was expected of me except that I enjoy myself (which, I suppose, was the case on the other trip, but it did not feel as relaxed). I am a big fan of lying down and availed myself of this proclivity for some time. We ate some of the food that my two hosts had prepared. We also took a walk to a nearby church, which was hundreds of years old, and the village store, where, it was explained to me, the local young people got together. The store was, architecturally, akin to those gas stations that you come across in the middle of nowhere, except that it was not connected, to the left and right, to a highway, but was surrounded by birch trees, a pond, and a gravel parking lot, where the aforementioned youth sat smoking on the hood of their car and talking loudly. It seemed like a strange place to me to hang out, but there was nowhere else, in this little colony of summer houses, to gather, and the general store was abutted by a little bar. It had only opened, my friend's cousin explained, a year or two ago, having begun with its owner's selling vegetables out of the back of his truck.

We had guests, my friends' neighbours, over for dinner that night. Those neighbours had a child of my friend's child's age, and I got to watch the two of them play, which was even more interesting when they were joined by the neighbour's thirteen-year-old girl, who had nothing to do and no problems cavorting with children younger than she. They had spent all day out in the fields doing God knows what--it was perfectly safe, as the thirteen-year-old was the serious, responsible type and could look after them--and did not even come in for dinner until it was already dark out. Our guests left soon after that, and I stepped out into the early night, which was so quiet that I could hear the river-like rustling of the trees in the distance and the calls of various very musical birds, the only one of which I could identify was the cuckoo.

The next day was hotter and a little more active. I had taken a brief turn at mowing the grass by scythe on our first day, as I was eager to seem like Lev Tolstoi and wanted some exercise, and, on the second day, I mowed almost the entire weedy section of my friends' plot, even decapitating a few of their blossoming flowers in the process. I lay down again for a nap, as I had had a hard day of relaxing, and, as evening began to fall, we headed back for the train station, buying fresh milk from a local farmer on the way. My friends would be heading back, naturally, by car. We said a hasty goodbye at the entrance to the train station, which one could only enter with a ticket, and, as my train pulled up, the three of them, my two friends and the one's daughter, waved to me from the overpass above the tracks.

That trip was the highlight of my second semester. My departure from Moscow as a prolonged nightmare, as it entailed the disruption of all of my routines and was leading me toward an unknown future. It was strange for me, in early June, living exactly as I had been doing before when I knew that I would soon have to empty my Russian bank account, pack up my stuff, sell or give away what I did not need, and leave the country for good. These weeks passed quickly, as I was feverishly trying to see everyone whom I could possibly fit into my schedule, and I needed to run a whole gamut of errands, each small when taken on its own, before I left. I threw out all of my notes from the year, including, accidentally, notes that I had been carefully taking about a work that I was translating, used up the last of my baking supplies, and took a last walk to the massive local park. I have, happily, very few distinct memories of this time, as I spent most of it feeling as though my head would explode and I would never finish everything that I had to do before leaving.

I hosted a little going-away party on the last evening of my stay in Moscow, inviting five or six close friends to have bread and whatever they brought with them in my dusty little room. I had not yet packed, naturally, and, when my friends left, having sensed that I was getting antsy, I packed slowly enough that I feared missing the last subway to the train station and, in a panic, got a friend of mine, who was smoking outside, to call a taxi cab for me. Two Korean students from down the hall with whom I was friendly came outside to see me off. One of them, a Ph.D student at Emory studying social realist literature, said, "It has been a pleasure getting to know you, and I wish you all the best in the future," while the other student, who had worked in human resources in Korea, spoke less Russian than the Ph.D student, and was planning to remain in Russia to work, said something forgettable, laughing as he shook my hand.

My taxi ride only cost 301 roubles. The driver was from a former Soviet Republic, had a bizarre last name, and spoke near-fluent Russian; he spent the ride telling me that Russians were very dissatisfied with their country's government and only ever really liked it when they scored one against the Americans. I waited for my train next to a homeless woman with yellow toenails. I had not managed to pack all of my luggage, having woken up a friend at midnight to leave a bunch of my stuff with her to be mailed later, and was not yet sure if I was ready to exit Moscow. I had made a great many friends there. I did not want to have to decide what my future life might look like. I had grown comfortable in the dormitory and was now going to spend each night, for the coming weeks, in unfamiliar surroundings.

So ended my year of study in Moscow. I have a lot to add in an epilogue summarising the experience. I have changed a lot since I left Vancouver. Perhaps my only point of note is unoriginal: we should look at every day--this is definitely unoriginal--as a little transformation. Being in a country for ten months, with a set start and end date, forces one to think more actively of one's transformation and to see it more clearly as such, but our ability to transform should not be limited to periods in which we face the unfamiliar every day. I hope to carry this idea forward with me and not to see the changes occurring within me as distinct points so much as part of a continuum that began when I was born and will end when I die. I thought a great deal of my childhood over the last few weeks of my time in Moscow and was generally more aware of time's passage. I suppose that there is a mystery in time's passage that we can only tap into once in a while when we are especially receptive to it and to the sensation that it engenders of our never being the same for any two distinct and different seconds of our lives.

Sincerely,

Max

|

| My interest in the world returns. Spring twilight. |

|

| Fantastic clouds on a spring day. |

|

| A display about Moscow's history leading up to VE Day. |

|

| Yet another shot of the Kremlin. Good God. |

|

| Wildflowers somewhere. |

|

| Crowds form in Victory Park for VE Day. |

|

| A memorial to Russia's fallen soldiers. |

|

| I swear that I baked more than just challah this year. |

|

| Gathering storm clouds over Red Square. |

|

| Yet another sidewalk advertisement. |

|

| A bronze statue of a couple's farewell at the train station. |

|

| A windy day in rural Russia. |

|

| This is a different side to the country. |

|

| Kids playing out front an old, decaying church. |

|

| A church, some trees, and a fork in the road. |

|

| Dirt paths. |

|

| The incredible azure of the sky the next day. |

|

| Village twilight. |

|

| The village sunset. |

|

| Here I am mowing in pink Latex gloves and someone's rubber boots. |

|

| One last view of the village skyline. |

|

| Geese crossing the road. |

|

| Twilight, as seen from near downtown Moscow. |

|

| Lots of poplar fluff. |

|

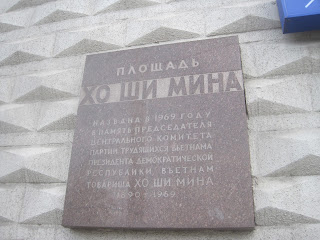

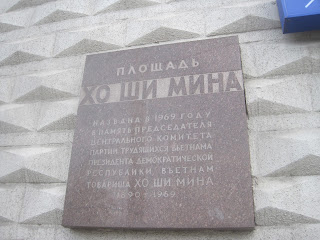

| Ho Chi Minh Square (in Moscow). |

|

| Much more poplar fluff. It was everywhere! |

No comments:

Post a Comment