My trip from Riga to Budapest began with an unexpected flight change: I had been scheduled to leave Riga at noon on June 30th and to arrive in Budapest four hours later, but LOT Polish Airlines moved the second leg of my flight, from Budapest to Warsaw, to the next day, July 1st. They had threatened, in an email, to cancel my flight, as they claimed to have been unable to get through to me about the change, but I had saved it by calling the company through which I booked it, for which I owe thanks to Skype for enabling people to make phone calls from their computers.

My expectation was that I would spend the night of June 30th in the airport, as I did not want to have to change a bunch of my money to Polish zlotys, make the trip from the airport to the city, and then come right back the next day. An airline official in Riga told me that I should look for a support desk in Warsaw if I wanted help, as they were not authorised, in Riga, to promise me accommodations. She was professional and did not charge me for my bag's being 23.5 kilograms. I had bought some black bread and dried figs, which I had improvidently eaten the night before, for my trip and had part of a bag of granola with me for the night.

When I got to Warsaw, I quickly found a help desk and complained about my predicament, first asking if there were any way for me to get to Budapest that night, and, upon learning that I could get in at 11:00 PM with a change in Munich, asking if they could offer me any food or hotel vouchers. The woman at the help desk made a couple of phone calls and was all ready to put me up for the night when, looking at my reservation again, she said, "You learned about the flight change two days ago." Here I kept a straight face and said, veridically, that I had been unable to contact the airline or make any new arrangements, as I did not have a phone with me (and one can only call 1-800 numbers via Skype), at which point she arranged for me to stay at the nearby Merriott, even giving me food vouchers for lunch and dinner. The hotel was only a three-minute walk from the airport's exit, and they checked me in immediately.

High-class hotels next to airports are too strange to be described in brief, but I have, alas, no time to describe this one in much depth. It is like a bubble in which one is insulated from the rest of the world: one is surrounding by smiling, efficient, knowledgeable staff trained to cater to one's every whim; the temperature and humidity of one's room, and of all of the hotel's premises, are carefully controlled; every surface shines, and the hotel is quiet, but one can still hear the hum of human activity, making it feel alive. The hotel had a gym on the second floor, of which I availed myself. Meals there were so big that I felt as though they were trying to kill me. I had a nicer room than I had probably ever stayed in and had access to fast, reliable Wi-Fi.

My flight to Budapest was easy, and I even arrived in the city well-rested. I met a young woman from Budapest on the bus into town who, when it became clear that I would not be able to make my way to the front of the bus to get a ticket, offered me one of hers, which I took with some embarrassment, as I could not very well pay her for it. She told me a little bit about the city and her studies in London, and, when we got to the edge of town, she offered me yet another ticket and rode the subway with me, as we were initially going in the same direction. Budapest's subway is not yet up to the standard of those in more modern European capitals: one cannot buy tickets in the stations themselves, but has to do so at nearby kiosks, and, instead of one's pressing them against a scanner to get into the subway, there are human ticket collectors who ask to see one's ticket when one steps inside. The subway is not badly marked, though, and one can find one's way around easily enough if one has taken the subway before.

My impressions of Budapest have been too varied for me to sum them up in any way. My first tourist activity here was to visit the House of Terror, which was awful (and expensive). It was about how much life sucked in Hungary during the years of communism and taught me nothing new. Someone at the hostel suggested that it had been dumbed down, to some degree, because using simpler language in the displays would help tourists whose native language was not English. Whatever the case, I was mostly dissuaded from museum visits after this one, having partly tired, over the past few days, of museums in general, and to spend most of my free cash on food.

There is no good black bread here, unlike in the pre-Baltic states. The stone fruits and sour cherries here are quite good. Of the local dishes I have so far tried beef stew, which would be fantastic with a proper cut of beef, and goulash, which is a bit of a tease, as it is so hot when one first orders it that one cannot immediately eat it, and one has to skim the fat off of the top of it anyway. I am going to try a trifle-like dish with a weird name, paprika chicken, and a popular fruit soup. I have not yet had ice cream on this trip, despite how good it has looked here, but have tried the famous poppyseed cake, which is good. Hungarians appear, based on the one restaurant that I have so far visited, to be anathema to vegetables, which may reflect that few vegetables were available to them historically due to the coil content of their farmlands.

In lieu of visiting museums, I decided to take a free walking tour here to learn more about the city. It turns out that the modern Hungarian state was founded in 896 when some king or other united the tribes living there (and Christened them, I presume). Celts, and then Romans, had settled in Hungary before the nomads came, attracted by its being protected on all sides by mountains and having plenty of spring water (which is what gave rise to the more contemporary popularity of baths here). Of the possible routes to growing rich--farming, fishing, being on trade routes, salt mining, spice production, and warfare (I gather that pottery and weaving could get individual families or villages rich but would do little for entire nations.)--the Hungarians chose the latter, warfare, amassing giant territories in the Middle Ages. The Ottomans conquered them in the early 17 century and were expelled in the late 18th century, after which point the Hungarians fought wars with their neighbours until signing a peace treaty with the kingdom in Austria in around 1853, forming the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

The formation of the Austro-Hungarian Empire required the foundation of a new, eastern capital, and the cities of Buda, which had a medieval fortress or two, and Pest, across the river from it, were chosen, and Budapest was born. The city grew quickly and was intensively developed for the 1896 expo in honour of the country's thousand-year history, at which new inventions, works of art, and technologies were shown off. Hungary was, at the turn of the century, as developed a nation as any other, but it was trashed during World War I (I do not know by whom; I do not know with whom it sided.), again destroyed in World War II (having been occupied by the Nazis), and wrecked definitively during the years of communist rule, in which its farmlands were misappropriated and stripped clean, its economy was flipped on its head, and its workforce was made to advance heavy industry despite a lack of any proper infrastructure for it, and all products of its labour were stolen from it. The country has been gradually rebuilding since 1991, but, through no fault of its own, it still has a long way to go; a tailor whom I met, the group leader for the city tour, sews her own clothes (i.e., the ones that she sells), as the textile industry was, like every other one, trashed during communist rule.

The architecture here is interesting. Because Budapest was formed so recently and mostly developed in the second half of the 19th century, much of its buildings are built after those of Paris' city centre, which seems to have influenced architecture all over the Western world. The buildings that I have in mind are those four or five storeys tall with broad, flat facades and a sort of scalloped trim, like the frosting on store-bought cakes, along the roof. The main site of the 1896 expo includes a giant column modelled after those of the Roman Empire, bronze statues of a bunch of kings riding horses, and one of those semicircles of columns, also modelled after some classical analogue to it. The old fortresses on two of Budapest's hills (on the "Buda" side) are old fortresses. There is a victory statue, smaller than the one made for the expo, up on one of the hills (as well, now that I think of it, as a semicircle of pillars with a king on horseback) on one of Buda's hills. It has the obligatory accoutrement of a cathedral, churches, and museums in the city centre, as well as a massive synagogue, which I did not pay the money to visit. One of the hostel employees here pointed out that statues, victory columns, and the like are usually built for people who won wars (i.e., conquered other peoples), not for those who have helped to further the common good for all human beings. I had thought of this before, especially in and around Saint Petersburg, where, looking at the lavish palaces in which the rich lived, one thinks of all of the poor who laboured to make those palaces possible to build, sleeping in wooden shacks and eaten slop for dinner after 16-hour workdays in the fields. The world is full of injustice, and I think that one's goal when travelling is, rather than condemning people for their iniquity, to understand them, as people everyone are flawed, and one could find cause to excoriate them all day long.

The only day-trip that I took on this trip was to Szentendre, a delightful touristy town near Budapest, which I reached by suburban train. Taking the train there would have been nearly impossible, as it was a weekend, and no one was working at the ticket counters (I do not know if anyone ever works there regardless.), without a hostel employee's giving me a rough sense of how to do it. (Also, a local helped me to find the station, while another one helped me to get my ticket. People here have been enormously welcoming.) The tricky part is in buying two tickets, one for travel within Budapest's city limits and one for travel without them, but staying on the same train: it is far from impossible, but one could probably incur serious fines by not doing it right.

The train ride itself was not bad, as it took us past Budapest's Roman ruins, which I was, before I got here, planning to visit, and Szentendre was magical. I felt, when I got there, as though I had stepped out of Hungary and into medieval Germany: it is a town of two-storey, several-hundred-year-old buildings with ornate facades, of little churches and cobblestoned streets, some of which lead down to the river, the Danube. Local craftsmen had set up stalls on the city's main street and were selling knickknacks of all varieties, food vendors grilled big, smokey chunks of meat, and bakers made traditional pastries shaped like corndogs without the dog, which are made of dough baked on a rotating rod (hence their being hollow), right on the street, so that the whole town centre smelled of baking dough and grilled meat. The tourist information centre was at the very entrance to the main street (from the train station, where everyone starts), the edge of town had one of those free outdoor workout spots (with chin-up bars, dip bars, and the like), there was plenty of green space, and there are even reminders of Szentendre's considerable Serbian community, which was kicked out something like a hundred years ago. I did not try any of the food there or the churches that cost money to enter, as I am on a tight budget, but I did visit what might be the smallest synagogue in the world. This I found more affective than visits to larger sites, as it told the story of a small enough community of people that the numbers meant something to me. Something like 279 Jews were expelled from Szentendre toward the end of World War II, when the Nazis arrived, of which only 36 returned. One of these started to build a synagogue but died in 1997, before it was done, and either his or someone else's grandson decided to continue building it in memory of the entire community. The synagogue had historic photos of some of Szentendre's Jewish photos and family relics. The woman manning it gave me a little kippah to wear as I entered it and tried to give me an information card in Hebrew before I explained that I did not speak it.

The rest of my impressions of Budapest, are, unfortunately, multifarious, meaning that I have a lot more to write. There was a gay pride parade here a few days ago, as a result of which the main street through town was fenced off (along with many streets nearby it, making it hard to get back from the city centre to the hostel here). Someone who had gone there explained that she was made to drink some of the water that she had brought in the presence of a police officer to prove that it was not a Molotov cocktail--non-participants were not allowed to come within a city block of the procession, and people leaving the parade were advised to hide their rainbow flags so as not to be attacked. I do not blame their behaviour entirely on communism's having destroyed their society, as the Hungarians were, historically, overwhelmingly, Roman Catholic, which, I believe, means that they are not supposed to like homosexuals. This, in itself, is confusing to me, as, if God made man in his image, and lots of people are lesbian, gay, queer, or questioning, than God himself, unless he screwed up the job of reproducing His image, is, Himself, lesbian, gay, queer, or questioning, meaning that the Bible, if I am not mistaken, condemns Him. I am glad that I am not religious, as these types of issues could tie me into all sorts of knots if I wanted to follow the religion punctiliously.

Impressions, impressions! I noted not having much time to write, as one spends all day sightseeing and much of one's evening exercising. People in hostels are often social, and many tasks take longer than it seems that they should. I visited a gym here that may have been aimed at homosexuals: all of the weights were in a windowless basement plastered with photos of very muscular men, who were, in fairness, all at least in a partial state of dress; the other men working out there were incredibly muscular, and the gym played some sort of rave music. Water here, as in all of Europe, is potable, putting Russia to shame. The main market here is pretty neat, though greengrocers there will not let one touch or smell their fruit, ensuring that they not be able to confirm its quality. There is an island here, Margaret Island, the whole circumference of which is lined with a track, as in a running track made of that pebbly, ruddy material that is good for one's joints. I have gone running a couple of times as the sun was setting over Buda, the older part of town. The sunset's slow unfolding reminded me of the ripening skin of a peach: it was a pale, still green just above the horizon, a little yellower above that, and a full-blown salmon pink higher up, licking the wisps of cloud with pale scarlet. The river water looked, at dusk, like a kaleidoscope of shifting black and white tesserae, and the hills farther off were so clearly outlined in the moist summer air as to appear to have been etched into the sky, as though both hill and sky were part of a diorama. Little stick-like trees, houses, telephone poles, and a TV tower stood out, depthless, on it, and, for some time, one could still see little spots of colour, people, running along the track from the bridge above before everything melted into a featureless murk.

There are, surprisingly, few mosquitoes in Budapest. It has free water fountains everywhere, including by the track on Margaret Island, and little outdoor gyms like the one in Szentendre. It is famous for its baths, which I did not bother to try, and its Jewish quarter, which I hoped to see on a free walking tour that I missed. This frustrated me, and so I read up on the history of Jews in Hungary on Wikipedia as penance--they were mistreated for hundreds of years, became part of the middle class from the end of the 18th century onward, and then were exterminated during World War II, though not as early as in many nearby countries, as the Nazis did not arrive until 1944. Although Hungary is not as developed as, say, Germany or France, it is now a flourishing society full of artists and scholars, and its shortcomings are largely the fault of the communists, whom I hate, just like the citizens of every former Soviet colony in Europe that I have visited. In Riga, I read the letter that some commander in the Soviet Army wrote to Latvia. While I cannot remember its exact wording, it said something like: "Dear Latvian people, our army is [some enormous number] strong. Your army has [some small number of people]. In the interests of uniting our peoples peacefully, we propose that you join us as a Soviet republic. This war has already been marked by enough bloodshed... &c." Similar letters to the rest of the future Soviet republics must have been written. Russian can go on priding itself for having formed the Soviet Union without force. They seem to be the only people on earth, surprisingly enough, to approve of the former Soviet rule.

I have learned to say "hello" and "thank you" in Hungarian but do not yet know any other phrases by heart, and I am unlikely to learn any, as I will be heading to Brno, in the south of the Czech Republic, tomorrow morning. I forgot to mention, in an earlier post, liking the parts of Christian ideology tied in with finding inner peace, reconciling oneself with the parts of one's life that one cannot control, wishing for a better future, and so on but dislike much of the thinking that goes along with it. I have noted, based on Russia's having one of the largest economies in the world and, thus, a high GDP, that a better measure for a country's development would be to subtract the wealth of the top one or two percent of the population, then look at its GDP, as the top one or two percent in practically every country live obscenely well, which says nothing about the bottom 98 or 99%. Gas in Finland cost something like 1.24, 1.34, and 1.43 Euros (for different types), if memory serves, while in Estonia it was closer to one Euro per litre. I have been blown away by how quiet it has been in literally every city that I have visited since leaving Russia, and it occurred to me the other day that the cause of the quiet is people's not leaning nonstop on their horns while driving. There are functional bike lanes, which tons of people use, here, and, like in Riga and Tallinn, people walk on the sidewalk and the sidewalk only, while, when it was asked on a popular radio show in Moscow if the city needed bike lanes, callers replied, "What do we need bike lanes for? We don't even have roads!" Someone whom I met in Tallinn said, when I described Russian society to him, "It sounds like they lack any vestige of the sort of cooperation that you expect in a cohesive society."

My only plans for today, now that I have seen much of the city, is to try more of the local cuisine, visit a swimming pool, and keep writing. I have not seen as many museums as I initially expected to do and have, at times, cursed myself for returning time and again to the same countries over the past few years rather than trying something new. It has occurred to me, though, that one can change more from a trip from Victoria than from a trip to Thailand if one has the right mindset. I often think of how I would like to redo much of the past several years of my life, planning my travels more rationally and saving more money, but I am willing to accept that past mistakes, if such they were, have helped to shape me. I plan to try a lot of local food in Vienna, where I will be staying for a day, and the Czech Republic, and I may visit a bunch of museums in Prague, in part to make up for having missed out on some stuff here, and in part because I will, after all, be visiting the city for a second time, and there is little to see by walking that I have not yet seen (I should think). One generally thinks a lot while travelling. I expect the coming days of my trip to be interesting and hope to get as much writing done as possible.

Sincerely,

Max

|

| One of Budapest's huge boulevards. |

|

| Fancy 19th-century buildings. |

|

| Hungarians like books. |

|

| Some sort of castle building. |

|

| This bakery was acceptable. |

|

| Budapest's cathedral. |

|

| Budapest has lots of amusing statues like this. |

|

| Budapest's palace from across the water. |

|

| The ruins of a castle on the same hill as the castle. |

|

| This appears to be some sort of wall. |

|

| Some important guy on a horse. |

|

| These look oddly like boysenberries. |

|

| A fascinating building from above. |

|

| The river from a bridge. |

|

| Historical Budapest turned sideways. |

|

| The famous parliament building. |

|

| This appears to be Szentendre. |

|

| People sell stuff on the main pedestrian street. |

|

| This guy appears to be deep in thought (in Szentendre). |

|

| An old back-alley in Szentendre. |

|

| This house was overgrown with ivy. |

|

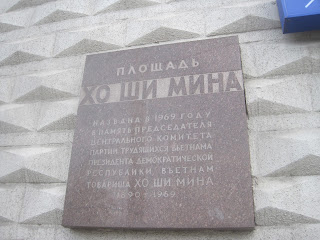

| A memorial plaque by the world's smallest synagogue. |

|

| Part of Szentendre from above. |

|

| One of those tiny chapels that Europeans used to build. |

|

| Heroes' Square, built for the 1896 expo. |

|

| These look like salal berries. (I did not, naturally, try them.) |

|

| I did not see a single one of these in Moscow. |

|

| A Holocaust memorial in Budapest's Jewish Quarter. |

|

| The famous synagogue. |

|

| The hill on which the freedom memorial rests. |

|

| Budapest from the aforesaid hill. |

|

| As above. |

|

| Another cool statue. |

|

| Shoes Along the Danube. Jews got shot here in 1944. |

|

| The parliament building, less imposing, from the side. |

|

| This appears to be for Liszt. His hands are huge. |

|

| Part of the Jewish Quarter--derelict facades. |

|

| This is, I think, a building in the park with monuments for the expo. |

|

| Evening light near where I was staying. |